For a few decades, Microsoft occupied one of the most privileged and profitable positions any company, in any industry, has ever enjoyed. The company was synonymous with personal computers throughout the era when they went from being rare and expensive curiosities to being ubiquitous devices in every home and office – yet it did not manufacture any computers of its own.

The actual process of manufacturing, distributing, and selling computer hardware (which is risky, capital-intensive, and generally low-margin thanks to high logistical overheads and fierce market competition) was carried out by countless other companies, not by Microsoft itself. Instead, each time one of those companies sold a computer to a consumer, Microsoft was paid a handsome license fee for installing the Windows operating system.

PC manufacturing was and remains a cut-throat business, and many of the companies that were once huge players in that space have either sold off their PC divisions or folded entirely, but the impact on Microsoft was minimal; manufacturers came and went, but they all still needed to pay for their Windows licenses regardless.

Nowadays, Microsoft’s business is much more diverse; Windows licenses are a relatively small part of it, and much of the company’s future growth prospects are in areas like cloud services and AI. Still, the model that built the company to the giant it is today – selling a dominant, high-margin operating system for computers built by other companies, while staying well clear of the risky, low-margin hardware business – isn’t easily forgotten. It’s an enviable position, one that most companies would probably love to be in, with arguably the closest modern analogue being Google’s Android operating system.

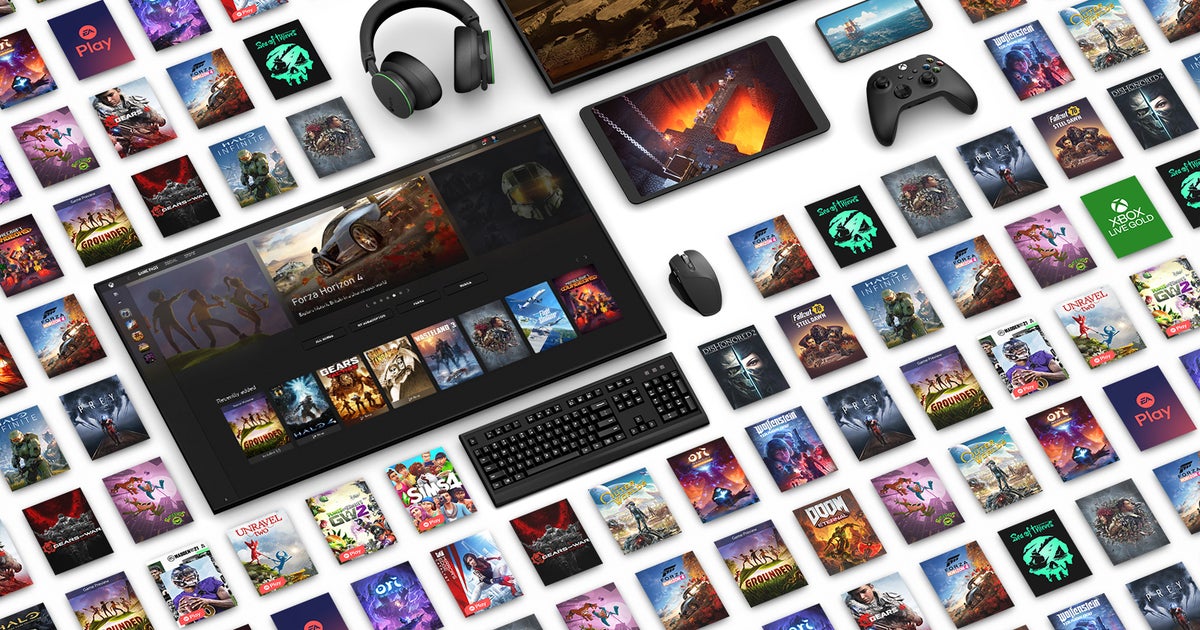

It’s always been quite clear that Game Pass – as the central pillar of Microsoft’s broader strategy to make Xbox into a software and services offering rather than “just” a console – was an attempt to achieve something similar in the videogame market.

When Microsoft CFO Tim Stuart commented at the Wells Fargo TMT Summit earlier this week that the firm would like to see Game Pass available on all sorts of devices, including consoles from rivals like Sony and Nintendo, he wasn’t saying anything new, per se. The idea of Game Pass being available on PlayStation or Switch has been floated repeatedly over the years. This idea, which would essentially position Xbox and Game Pass similarly to Windows’ historic position on PC hardware, being reiterated by Microsoft’s CFO is still interesting, though – in part because it speaks to the strategic thinking about games at the company’s highest levels, and in part because of how unrealistic the whole idea is.

For all that the frontline warriors of the console war make it seem like Xbox versus PlayStation is a life and death struggle, Microsoft’s top brass doesn’t actually talk about games very much, largely because the company’s big investors also tend not to ask about that side of the business very often in public forums. That makes any insight into how the company’s central decision-makers are actually thinking about games very valuable, even if it’s only confirming what we already knew – in this case, that the ultimate strategy for Xbox is one in which Microsoft’s gaming software and services will ultimately be distributed across a wide range of highly commoditised hardware manufactured by other companies.

Some aspects of that aspiration are realistic, at least in the medium term; putting a version of Game Pass that relies exclusively on XCloud onto devices like smart TVs is certainly within reach, for example. In the EU at least, there’s a possibility that new regulations on app stores will also provide a route for doing something similar on smartphones.

The idea of Game Pass running on Sony and Nintendo hardware, though – that’s going to be a hard sell, and the obstacles that stand in the way of something like that happening are not purely financial.

It’s tempting to link this situation to the issue that’s been litigated in courts around the world for the past few years; the question of how much and to what extent it’s justified for a platform holder to charge a toll for access to their platform. Lots of companies are currently chafing against the rather arbitrary 30% fee that has become commonplace across most platforms. In an era of cost-cutting, it’s one cost that refuses to disappear, which has led to a variety of legal actions being taken by companies exploring ways to minimise or circumvent it. Still, if Microsoft were willing to pay such a toll – willing to hand over a 30% cut on the portion of Game Pass revenues attributable to Sony, Nintendo, Valve, and any other platform holder whose hardware they wanted Game Pass on – wouldn’t that overcome the biggest obstacle to this happening?

To be clear, I doubt Microsoft is even willing to go that far right now – forking over a third of its Game Pass revenue on those platforms could significantly affect the service’s profitability – but even if it was willing to do so, I don’t think the deal would be remotely appealing to most of the company’s games industry rivals, nor would it be particularly welcomed by many game publishers or developers.

The problem is that companies like Sony, Nintendo, and Valve (whose Steam Deck is arguably the most likely rival platform to welcome Game Pass in the foreseeable future) are not like PC manufacturers in the Windows era – they are not companies who derive their profits from margins on hardware sales. Their business (Sony most of all, Valve somewhat less than the others) is selling game hardware cheaply and making back their money on software sales. If allowing Game Pass on their hardware displaced more software sales than could be covered by a hypothetical 30% cut of the revenue, it would be a terrible deal for them.

Even if Game Pass did pay for itself in this regard, it could still be a terrible deal, because it effectively commoditises their hardware. As Game Pass becomes an increasingly important conduit for people to play games, their choice of hardware would matter less and less – who cares whose console hardware you’re using, if the service you play games on is universal anyway? Even if their own first-party software helped to maintain their position in the market, such a scenario would destroy a significant part of the brand loyalty Sony and Nintendo have spent so much time building up.

It’s not just Sony or Nintendo that stand to lose out from Game Pass becoming increasingly ubiquitous, though. Valve does seem to be more open to the idea of Game Pass on the Steam Deck than other rival firms, and while I suspect that Valve’s openness to the idea is somewhat performative, as it likely has some fairly strict red-lines and favourable terms in mind for any potential negotiation with Microsoft on this front, the notion has still caused a stir of disquiet among many developers.

It’s still not entirely clear how much Game Pass cannibalises sales in other channels, not least because the answer seems to vary dramatically from game to game, but in general developers seem to have found that putting a title on Game Pass still allows them to enjoy solid sales on Steam. Allowing Game Pass onto the Steam Deck wouldn’t end that, of course, but it would erode it; it would push more and more consumers towards a game subscription model that creators are perfectly comfortable with as long as it provides additive revenue, but which becomes an existential threat if it’s instead cannibalising the much, much higher revenue they receive from sales on Steam and other storefronts.

We are currently watching the movie and TV industries desperately try to pick up the pieces after years of hugely damaging missteps with streaming services. These industries have locked themselves into business models that are inherently less profitable for almost everyone involved, a result of “disruptive” moves by companies that only exist because of multi-billon dollar land grabs with major investment backing.

With the land grab phase ending and investment drying up, those models are turning out to be pretty much unsustainable, and companies find themselves desperately trying to cut costs in order to square this impossible circle. The music industry has done something very similar – in other words, we have lots of examples of how not to do this transition (or perhaps why this transition should not happen at all) to look to.

Tim Stuart has reiterated an ambition that makes perfect sense for Microsoft; especially in the wake of the supply chain nightmares that showed just how risky and difficult the hardware business is, why wouldn’t it aspire to being the company that makes money from software and leaves the hardware work to others? While it’s his prerogative to hold that ambition for his company’s games business, though, it would be madness to expect the rest of the industry to fall in line with a plan that’s not in their interests today, and may end up being hugely destructive down the line.