It’s almost twenty years since Steam evolved from being an automatic patching system for Valve’s games into being a digital storefront for third parties, heralding the true arrival of the digital distribution era that had been forecast for years prior. We’re now all living in the future that Steam ushered in, for better or worse.

Digital distribution is now essentially the default for games on all platforms; it’s the only way to get games on smartphones and tablets, and some PC and console titles never get physical releases at all. There are even digital-only editions of consoles in this generation, flagging a potential future in which physical media will be dropped from game hardware entirely.

When this future was still on the horizon, there was immense optimism around its possibilities – and especially about the extent to which it would democratise the games business, eroding the authority of publishing gatekeepers and opening up market access to a much wider range of creators. It’s fair to say that while the manner in which this has been achieved is deeply imperfect, digital distribution has more or less lived up to that goal; compared to the time before its introduction, when the very concept of an ‘indie’ game seemed rather wild, we now have vastly more open markets and accessible platforms, leading to a much wider variety of games from a far more diverse set of creators than would have been possible before.

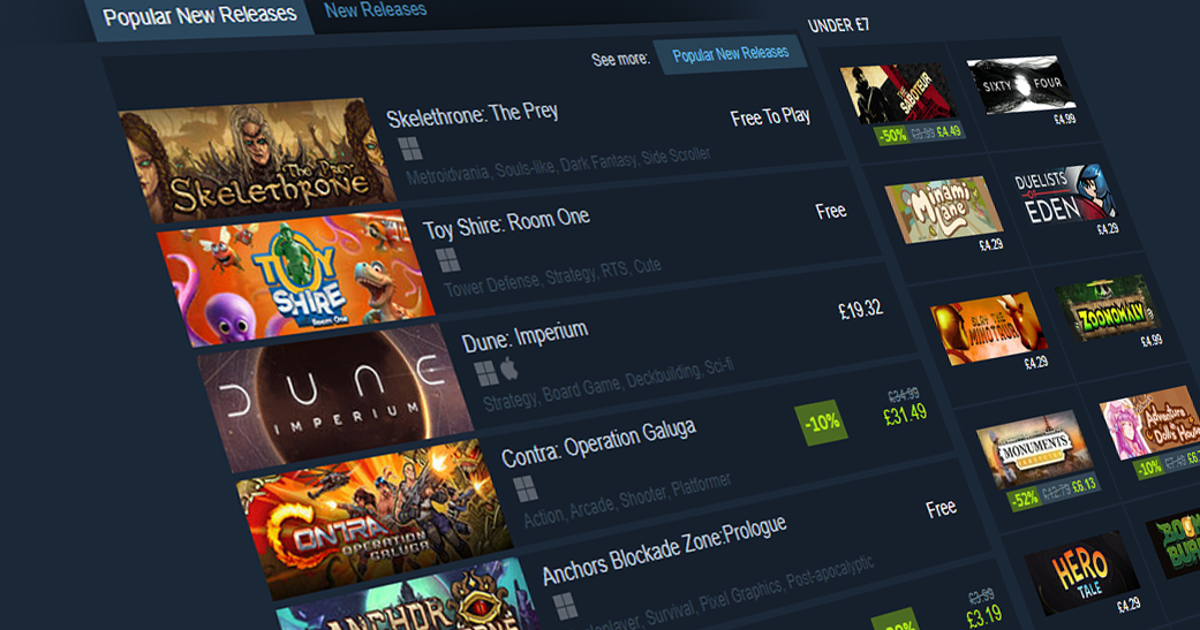

One big problem, however, emerged in the early years of digital distribution and has never been satisfactorily solved – not by any of the myriad platform holders on any of the devices in which digital games now hold sway. That issue is essentially the problem of too much success; there are too many games competing for consumers’ attention, and this creates an enormous challenge for discoverability.

How to deal with this – how to present consumers with the games that will interest them the most, while keeping the playing ground fair and open for developers releasing games on these platforms – is a thorny multi-faceted challenge that has been worked on now for literally decades, with everything from better UI design through to smart learning algorithms being applied to try to improve things. We are still, however, impossibly far from any kind of perfect solution – which may be simply because no such solution is possible.

This week brought a fresh reminder of how tricky the problems around discoverability can be, even on platforms that have worked very hard on this issue.

A short while ago, Electronic Arts released a batch of its classic PC games – titles like Command & Conquer, Dungeon Keeper, and Sim City – on Steam, much to the delight of fans of these retro titles, who promptly bought them in large numbers, driving them en masse up into the higher echelons of Steam’s charts. So far, so good – except that in the process, a number of indie developers’ recently released games were pushed down those charts, effectively knocking them out of one of Steam’s main discovery systems.

That would suck even if the charts were a simple objective count of sales, but these lists are designed to aid discoverability rather than recording a sales count; they list ‘New and Trending’ games, and giving new releases a boost by putting them on users’ homepages is part of the reason for such a list to exist.

One of the developers of an affected game – Renee Gittens, whose game Potions coincidentally launched at almost exactly the same time as EA’s releases – took to social media to lament the situation, pointing out that having worked on her game for years, she timed its release carefully to try to take advantage of weekend sales, only to be flooded off the discovery lists by EA’s games. Gittens’ video attracted a ton of publicity and millions of views, so I guess in some small way things have turned out alright in the end – more people probably heard about Potions and saw its launch trailer as a result of this situation than would have seen it otherwise.

That does not in any way address the deeper issue here, however, which is the precarity of the situation exposed by these events.

Games shouldn’t be coming to market relying almost entirely on discovery tools that could bury them in an instant based on an entirely unpredictable business decision from a third party – nor should their success be conditional on the ability to express your frustration and despair to win attention. It’s great that Gittens’ lament has probably snatched victory from the jaws of defeat here; it’s not good at all that she had to do so in the first place.

EA obviously isn’t the bad guy here – on the contrary, it’s wonderful that they’ve released this slice of their back catalogue, and it would be great to see even more releases like this. But Steam isn’t even really the bad guy here either, even though it’s objectively insane that, for small indie developers, the reality is that years of work can live or die by an extremely arbitrary ranking on a Steam chart in the two or three days after launch.

Steam has legitimately tried to improve this situation, but it has run up against challenges that have stumped most of the world’s biggest and smartest companies. If anything, the situation is even worse on other platforms like the iOS App Store or the Google Play Store, and it’s a problem that’s replicated across almost every open media marketplace, from YouTube to Amazon’s Kindle publishing platform.

There are actually two related problems here – one of which is gradually being solved, and the other of which may never be solved. On the one hand, there’s an issue with these platforms being flooded with low-quality dreck – which is increasingly being churned out by generative AI, making the problem even worse, especially on platforms like Kindle. This makes the signal to noise ratio pretty terrible and can drown out genuine, decently made releases. That’s an issue which platform operators do try to address, with varying levels of both effort and success; Steam has arguably done better than most on this front.

That only exposes the bigger and more intractable problem, though – which is that even if you did somehow cut out all the dross, there’s simply a ton of stuff being created and released. There are so many creators out there seeking an audience, and only so many audiences to address. There comes a point where it’s no longer a question of discoverability, but rather of the attention economy itself.

There’s no tweak Valve or any other company can make to its algorithm that will miraculously give consumers more attention to dole out, more hours in the day, or more money in their wallets. Competition for that attention is real, and it’s ferocious, and that’s not something that can possibly change no matter how smart the platform algorithms get.

You could reasonably argue that EA’s classic titles don’t have the same discoverability challenges as a small indie game and shouldn’t have been in the same ranking lists as brand new games to begin with. That would be fair comment, and is perhaps another tweak Valve could look at making – but the broader issue goes beyond this specific context. I don’t wish to victim blame, but I think it’s reasonable to point out that a lot of creators – especially the kind of creators who work alone or in tiny teams on passion projects – tend to be really bad at marketing and PR for their creations. Their dismissive attitudes to this whole side of the business leads to decisions like just putting the game on Steam and assuming the new-and-notable chart will do its magic.

Some are simply unfamiliar with how to do marketing; others, perhaps, are uncomfortable with the kind of communication and self-promotion required by this side of the work. These issues often express themselves in the misguided notion that the quality of their work will “speak for itself”. Speaking for itself won’t do a damned thing if the room it’s speaking to is empty; for a work’s quality to speak, it first needs an audience to address.

Discoverability is a battle that never ends, and there are many areas that could still be improved – but there’s no magic wand to be waved here. There’s just no such thing as an algorithm that’s going to pull indie developers from obscurity and put their lovely games in front of just the right audience. Sweeping away the trash from major platforms is an ongoing task that some companies are doing better than others, but even with that perfected, the struggle to win attention from the right people to make a game into a success is going to be hard work – and it’s going to require skills beyond game development, in areas like marketing and PR that some idealistic developers tend to view with more than a little side-eye.

Sometimes, those skills are just going to be about figuring out the right tone and presentation to turn lemons into lemonade and make your game being buried in EA classics into a major PR coup; but not everyone has that kind of nous, or that kind of opportunity. For most indies – and even some larger developers – spending a bit more time and resource focused on market research and marketing strategy will be a very, very worthwhile thing to do.

Nobody is going to solve discoverabiity for you; the only answer is to figure out for yourself which rooftops you need to be shouting from.