Business pundits and analyst investors have hit the airwaves to try and explain why so many jobs in the tech industry have been lost. The consensus is that this is a correction to the wave of hirings done during the pandemic. Back then there was a need to invest in technological solutions to address working from home and technical alternatives to systems that otherwise would not be needed if there was no pandemic. Tech companies needed to hire more people because their businesses were in greater demand. The extra money that went their way resulted with more bodies hired.

But by 2022 the business cycle began to return to “normal”. People left their homes without masks and the pre-pandemic daily routine was slowly, but surely, coming back to life. This also meant the projected increase in revenue for tech companies either slowed or was revised with a lower number. For some, revenues began to reverse.

A loss in revenue for any private company is not great, but these losses are often mitigated by the management who have a direct stake in the business. A loss in revenue for a publicly traded company is another matter. It becomes a disaster for investors who only want, or expect, constant growth in profits. Something, therefore, had to give, and that something was jobs.

The analysts picked up on inflation, which applies to all industries, and most other industries are not shedding jobs by the tens of thousands; higher costs of borrowing (again that affects all industries); investment ceilings being reached; and tech companies getting ahead of themselves for the “expected” recession when demand for their products wane.

In the last two weeks the news of mass redundancies from Amazon, Alphabet and Microsoft feels like a reverberation from the job culls at the backend of 2022. The cycle started when both Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerburg decided tens of thousands of employees had to go. Although the job losses were for differing reasons – one that did not make sense (Twitter) and one that did (Meta) – the cat was out of the bag. Job losses were needed to “re-align” businesses. In both cases it came from mismanagement in trying to pivot their core business into new revenue making ideas, and misfiring.

In Satya Nadella’s blog to Microsoft employees, the redundancies were needed so that the company can double down on its core business, while at the same time, seeking new opportunities in technological investments elsewhere. It would seem Microsoft is trying to have its cake and eat it. Namely what he is saying is that the job losses today are needed to secure Microsoft’s financial health in the future, with fewer employees. Ultimately that message is not for the likes of you and me – it was for the hedge funds, investment houses and banks who have money in Microsoft. The signal to investors is that job losses are not a bad thing, per se, if the goal is to re-align the business back into profitability (or in some cases, more profitability).

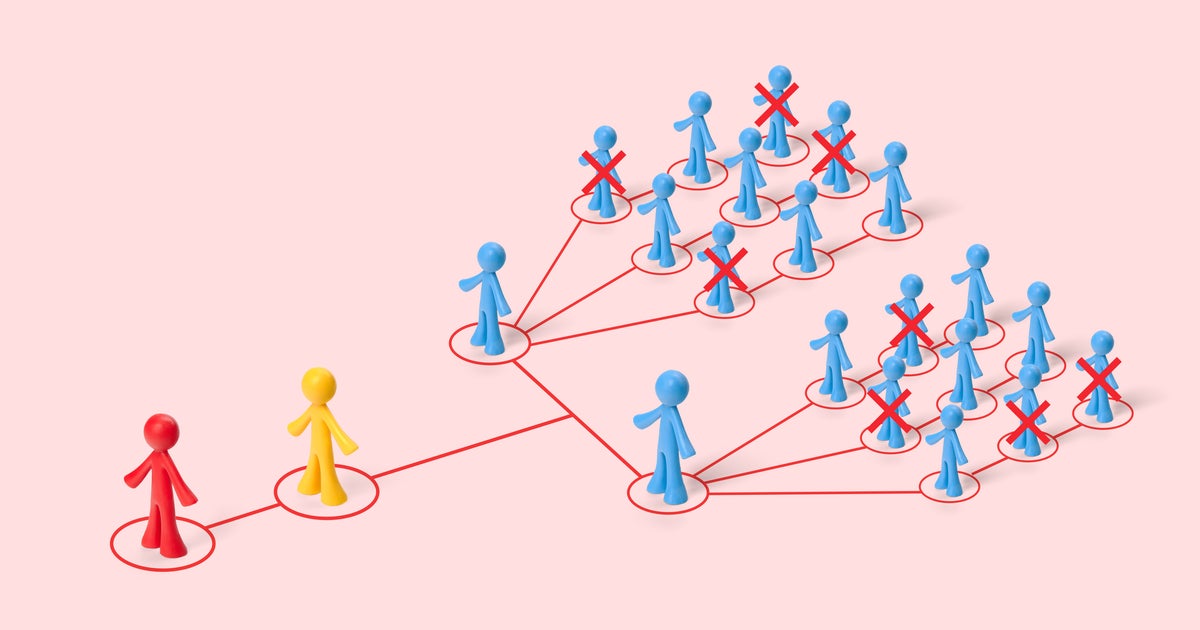

After the COVID party of expand, expand, expand, came the hangover of cut, cut, cut, all for the sake of the greater good of the company’s financial security. When Twitter and Meta cut jobs, investors were asking questions from their technology corporations: ‘Well – if they are doing it, why aren’t we?’

Suffice it to say the optics does not look great when a lot of these multinational companies continually post multi-billion-dollar profits. It is especially egregious from Microsoft after it publicly announced it will layoff 10,000 employees while simultaneously investing $69 billion in acquiring Activision and another $10 billion on investing in ChatGPT. There is also the fact that there is a kind of herd mentality going on with these corporations. Companies are aiming to hide their bad news amongst the clutter of other bad news announcements.

All of this begs the question, is the video game industry immune? The short answer is no. The long answer is, it’s complicated.

We have seen job cuts from Xbox teams including 343 Industries, Unity, GameSpot, Giant Bomb and Riot Games, but so far, no massive layoffs have been announced across the board. I think this is because the video game industry has one foot in technology industries and one foot in the entertainment profession. Ultimately video game developers, studios and publishers are in the hit-making business, a very similar concept to film.

Revenue comes from either new games, catalogue games, microtransactions, live services or subscriptions. Catalogue games can be classified as dead investments; namely the labour that went into making these games has been accounted for. Catalogue games require fewer patches and post launch support, so the staff to maintain them is minimised. Microtransactions and live services can require teams which could scale from large to skeleton, depending on what is being worked on. If teams need to scale up, contractors are often the best bet to fill in short term gaps.

Subscriptions revenue ultimately rely on new game content to keep them relevant. This means that the vast bulk of labour in video games goes into creating and supporting “new content”. That new game content revenue is not yet realised until release (barring revenue from Early Access or crowdfunding). For the vast bulk of new games, revenue is recognised at the point of sale, unlike products which offer technological solutions and have a higher booking revenue.

Although video games release in the world of “big tech”, they are also essentially pieces of art. Video games, by their very nature, are subjective. Either you like them, or you don’t. They are not essentials, but luxuries. They serve no purpose but to entertain. This means it becomes difficult to quantify their future revenue.

Some games outperform sale expectations, boosting profits, while others can bomb when release, drying up their company’s coffer. Just recently Krafton, the publisher of hugely anticipated The Callisto Protocol, had to significantly lower sales expectations when the game failed to meet its higher-than-expected target. On the flip side, Pokémon Scarlet And Violet, broke sales records for the franchise when the game released with reports of bugs and issues in gameplay. Go figure.

Revenue forecasting becomes less science and more esoteric. Hollywood has been grappling with this problem since the 1980s. William Goldman, the screenplay writer, put it perfectly: “Nobody knows anything…… Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work. Every time out it’s a guess and, if you’re lucky, an educated one.” That can also apply to video games. There is also the added issue that the video game industry is somewhat resilient to a downturn in the macro economy.

Historically, the games industry has never been shy in culling jobs or closing studios, but the reasons have less to do with macro economy conditions or what other tech companies are doing, and more to do with the sales performance of a new game. At times these closures often happen when the economy is doing well, and the mainstream tech industry is on a hiring spree. This is because the video game industry follows its own destiny in revenue planning. Its business cycle is very much governed by the lifecycle of consoles, trends in gaming, consumer behaviour and if the games are any good.

Publishers and game studios cannot cut too soon during development times because games, the sole revenue driver, still need to be developed. Often publishers will work to their own time scale and release dates. At times the problem for game studios is a lack of headcount, not from having too many employees. The “crunch”, when coders work under huge pressure to get a game out for a hard deadline, has plagued the industry for some time. If anything, publishers need more people, not less, when the crunch happens, but the time it takes to train people to be their most efficient is not there either.

The issue of video game employment security is when the game gets released and is in the public domain, not before. If the promised revenue fails to materialise than the publisher or game studio will have to make those “painful decisions” (which will most likely affect developers and lower to mid-level management). Given that the development time cycles and release dates for new games for each publisher will be unique, job losses could come at any time, instead of the waves of job losses that we are witnessing today among the big tech companies.

Similarly, new studios and development houses crop up all the time, and that is before we delve into hundreds of thousands of cottage indie game studios. They all create jobs. A glance at video game vacancies on LinkedIn or Indeed.com will bring back hundreds of results. In the video game world, there is no point following suit on what the next publisher does, or is not doing, when it comes to job hires and job cuts. The industry is simply too dynamic to follow thy neighbour.

Ultimately this boils down on how the revenue is generated. The job cuts in big tech are with companies that make their money, which is substantially different to the entertainment sector. They come from either online advertising, R&D in technology, recurring subscriptions or from applied science solutions. They don’t come from art. It is because the video games industry is fundamentally straggling two industries, technology, and art, that gives it its strength, as well as exposing its Achilles heel.

To sum up, job losses in the video game industry will continue to happen, but it will not be not because that is what investors are calling for, it will be because the games themselves underwhelmed. With 2023 expected to be a bumper year for games, hopefully any job losses in this sector will be mitigated.